Happy/Unhappy Anniversary, Scopes Trial!

Just in time for the centenary of John Scope’s conviction for the crime of teaching evolution, creationists have scored another win—this time in the U.S. Supreme Court. And they didn’t even have to show up in court.

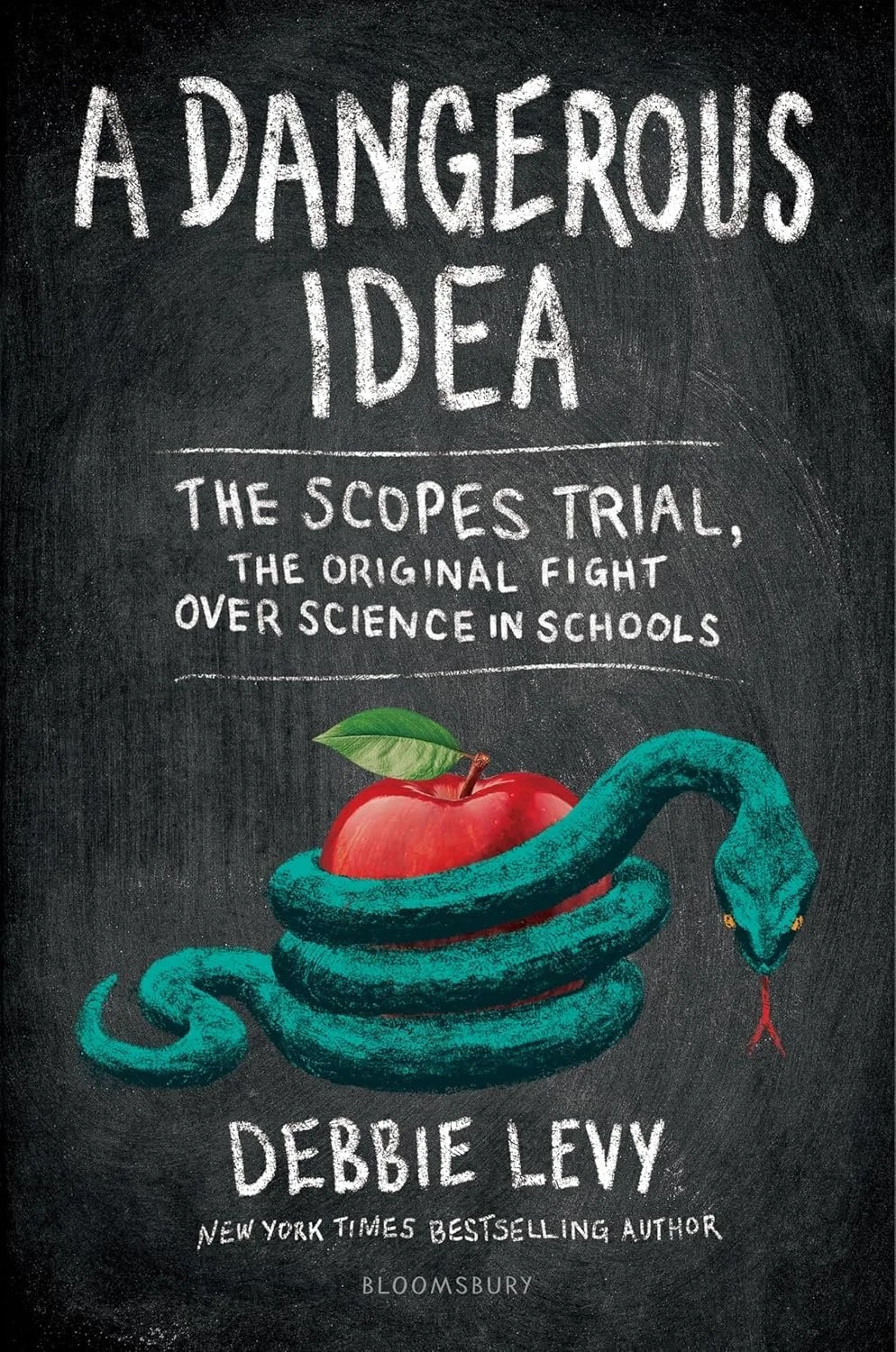

A hundred years ago this week, a high school science teacher named John Scopes was sitting in a stifling hot courtroom in Tennessee, on trial for the crime of teaching his students about evolution. A few years ago when I started work on A Dangerous Idea, my book about the trial, my main goal was to tell an engrossing true story that young adults and their parents could dive into.

Yes, the story shows how the Scopes trial foreshadowed modern problems of misinformation and disinformation.

Yes, it illuminates the thin line between substance and show, the disruptive force of science, and the high anxiety of parents about what their children might learn in school.

Yes, the story confirms that restricting thought and banning books have long histories in this country.

But I did not think the very subject of my book—whether parents could upend the teaching of evolution because it conflicts with their religious beliefs—would be revisited.

I was wrong.

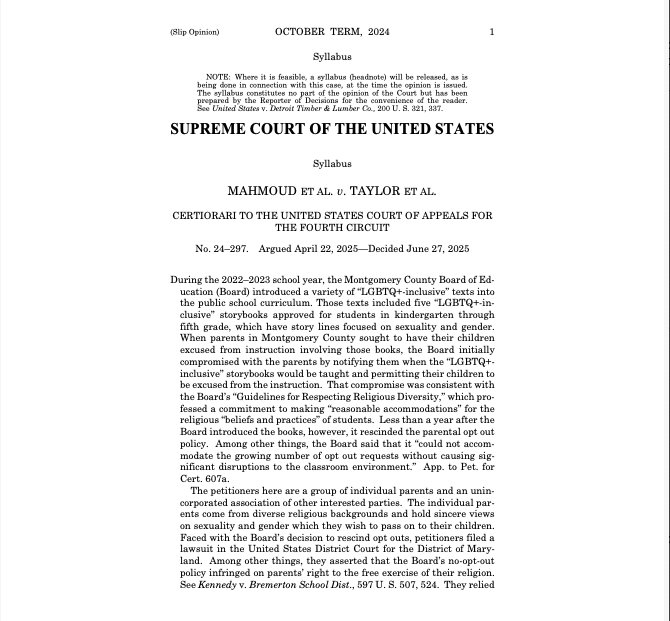

The same week the book hit the shelves this past January, the Supreme Court took on the case of Mahmoud v. Taylor. Last month the court issued its decision. And just in time for the centenary of John Scope’s conviction, the anti-evolution movement has scored a modern victory—without even showing up in court.

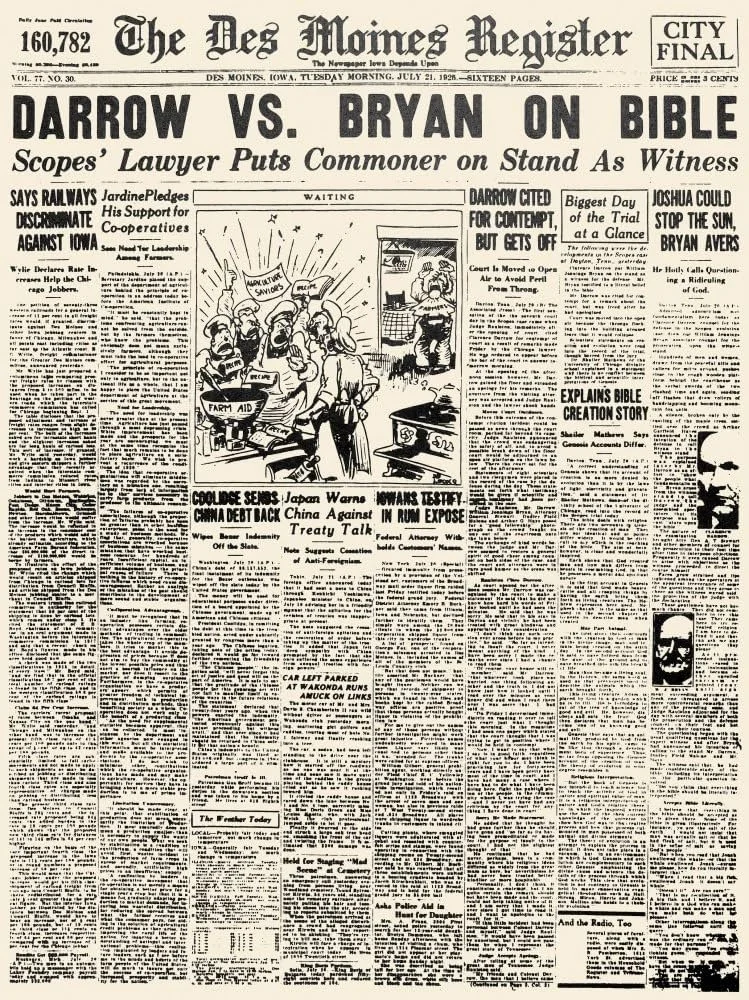

The trial of John Scopes is remembered mostly as a clash between two titans: William Jennings Bryan—the three-time unsuccessful presidential candidate and former secretary of state—who viewed the teaching of evolution as a menace to America’s youth; and Clarence Darrow, who I would say was America’s greatest criminal defense lawyer, and who viewed Bryan as a menace to the intelligence of the nation’s youth. You may remember it from the fictionalized account that became the famous play and movie “Inherit the Wind.”

At the center of the prosecution’s case was a notion of parental rights that reverberates a century later. “The Christian believes man came from above,” Bryan argued in court, “but the evolutionist believes he must have come from below. . . . Tell me that the parents of this day have not any right to declare that children are not to be taught this doctrine?”

The most powerful response to Bryan came not from Darrow, but from his co-counsel Dudley Field Malone. “We say ‘keep your Bible,’” Malone urged in the best speech of the trial. “Keep it as your consolation, keep it as your guide, but keep it where it belongs, in the world of your own conscience”—not as a substitute for science class. Teachers, he said, were not conspiring “to destroy the morals of the children.” Churches, he reminded his listeners, were not the only sources of morality.

“And I would like to say something for the children of the country,” Malone continued:

“I feel that the children of this generation are probably much wiser than many of their elders. . . . We have just had a war with twenty-million dead. . . . Civilization need not be so proud of what the grown ups have done. For God’s sake let the children have their minds kept open—close no doors to their knowledge; shut no door from them.”

When he finished, the packed courtroom erupted in cheers—and it was full of church-going people, including Fundamentalists.

But the trial judge decided that parents did indeed have the “right to declare” that their high-school-aged children not learn evolution. The judge upheld the law, and a jury of his peers convicted Scopes.

Baltimore Sun, July 19, 1925

And then—evolution pretty much disappeared from high school biology textbooks and classrooms for decades. It wasn’t because of anti-evolution laws; they didn’t sweep the country. But in many places, anti-evolutionists didn’t need new laws. Local school boards simply went ahead and nixed evolutionary curriculum. State textbook authorities rejected science books that included evolution.

And those books themselves evolved. Publishers aren’t in the business of courting controversy. After John Scopes’ trial, publishers changed their textbooks by deleting chapters on evolution and Charles Darwin. By 1940, high school science classes all over the United States had evolved in evolution-free zones. It took a nation-wide scare over the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957 to wake American adults up to the dangers of a nation of science-illiterate students. That satellite launch by America’s main rival was a shock to the public. How could the Soviets have outperformed the U.S. in the technological race to space? By the early 1960s, evolution was finally back in biology books.

Mahmoud v. Taylor is about sex, not science, centered on the Montgomery County, Maryland school system’s use of LGBTQ-themed picture books in elementary story times. Some parents found these books at odds with their religious beliefs, and sought to opt their children out of story time. The school board said no and the parents sued, claiming violation of their First Amendment right to the free exercise of their religions.

It was clear to me, and, really, to anyone who listened to the oral arguments in Mahmoud v. Taylor in April that the parents were going to win their case. Most of the justices seemed uncomfortable, and some appalled, at how Montgomery County had treated the complaining parents. But as is often the case when a government action butts up against a constitutional right, the important question was where the justices would draw a line.

The answer is, they didn’t.

Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, Born Ready, Prince & Knight—these were some of the books at issue in the case. They’re all a far cry from Darwin’s On The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. But an exchange at oral argument between Justice Elena Kagan and Eric Baxter, the lawyer for the parents, made their connection clear:

“I’m interested in what the nature of the rule you’re asking for is,” Justice Kagan said. “I mean, when you started, it was—it was about, you know, matters pertaining to sex. But . . . in the end, is what you're saying: When a religious person confronts anything in a classroom that conflicts with her religious beliefs or her parents’ that—that the parent can then demand an opt-out?”

Baxter confirmed that understanding.

“So,” Kagan continued, “this is a rule that applies as well to a [parent of a] 16-year-old in biology class saying . . . I don’t want my child to be there for the classes on evolution or on other biological matters which conflict with my religion? It would apply just as well to that?”

“We know that those don’t happen very often . . . .” Baxter began.

“But it would if there were?” Justice Kagan interrupted.

“Certainly,” he confirmed.

Later in the colloquy, she continued to press Baxter for some idea of where, if anywhere, he would draw a line: could parents insist on opting out of all subjects, for students of all ages—provided, of course, the parents held a sincerely held religious belief that animated their objection to the curriculum? Without some line-drawing, “It’ll be like, you know, opt-outs for everyone,” she worried.

Baxter didn’t have an answer, other than to say that he didn’t think there would be “floods” of parents seeking to exclude their kids from objectionable lessons. Justice Samuel Alito threw him a lifeline, observing that what made this case special was that “it concerns sex and—and gender,” subjects that raise “special concerns.” Baxter agreed.

But when Alito wrote the opinion for the 6-3 majority in Mahmoud v. Taylor, he never mentioned “special concerns” as a possible limiting principle. He announced no limiting principle at all. Instead, he formulated a broad rule: the question is whether the challenged curriculum would “substantially interfere” with a student’s “religious development” or pose “a very real threat of undermining” the religious beliefs a parent wants to inculcate.

Remember William Jennings Bryan’s cri de coeur: “Tell me that the parents of this day have not any right to declare that children are not to be taught this doctrine? Shall not be taken down from the high plane upon which God put man? Shall be detached from the throne of God and be compelled to link their ancestors with the jungle, tell that to these children? Why, my friends, if they believe it, they go back to scoff at the religion of their parents!”

No doubt Bryan, and the many millions of Americans today who believe that God created humans within the past 10,000 years, would say that hearing about evolution in a classroom “substantially interferes” with their teenagers’ religious development. Surely they would insist that evolution poses “a very real threat of undermining” a student’s acceptance of a literal reading of the biblical Creation story.

Mahmoud v. Taylor is about parents’ rights to opt their children out of reading books with messages that conflict with their religious beliefs; it doesn’t say that the parents can shut down, say, the teaching of evolution entirely. But as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissent (joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson), “Few school districts will be able to afford costly litigation over opt-out rights. . . . the foreseeable result is that some school districts may strip their curricula of content that risks generating religious objections. . . . Next to go could be teaching on evolution, the work of female scientist Marie Curie, or the history of vaccines.”

It happened for decades after 1925. It could happen again in 2025.